As you drive along the

A664, Edinburgh Way, on the outskirts of Rochdale,

Lancashire, you pass under a blue railway bridge. The

sign on the bridge welcomes you to Rochdale "birthplace

of co-operation".

The town is famous around

the world as the home of the co-operative movement, and

it would be reasonable to assume that this is a town

founded on harmony. The truth is that this co-operation

did not come easily. In fact, it was only achieved after

a tumultuous one hundred years of sometimes chaotic

action during which the world order was forever changed.

The so-called "Rochdale Pioneers"

opened their famous Co-operative shop on Toad Lane in

1844.

To observers in the 21st

century, it might be easy to assume that this

represented a stage in the development of the retail

industry. In fact, it was an important step in the

social and political change that was taking place

throughout Europe, and in which the people of Rochdale

can justifiably claim to be leaders.

In the period between 1750

and the opening of the shop on Toad Lane, three major

forces were instrumental in bringing about change in

Rochdale and across the country. These forces were the

Industrial Revolution, the church, and the campaign for

universal sufferage, the right, it must be added, for

every male to vote in parliamentary elections.

As Shakespeare wrote in

Julius Caeser, "There is a tide in the affairs of men

which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune" and for

Lancashire that flood was the Industrial Revolution and

for some it was a time of great fortune. Rochdale was

forever changed by this tide, but that isn't where its

history began.

The Early Years in the Parish of

Rochdale

Just how old the

Rochdale community is remains to be shown, but under

the name of Recedham it was mentioned in the

1086 Domesday Survey. St. Chad's, the Rochdale Parish

Church, had its first vicar appointed in 1194, but

there is physical evidence that a "church" existed on

the site long before the present one. In 1251 the town

was granted a market charter. Rochdale is indeed a

town of some antiquity.

The status as a market

meant that Rochdale became a trading centre for the

predominantly rural population that lived on the

surrounding moorlands. The introduction of sheep into

the local agricultural economy started a woolen

industry founded on farm-based hand spinning and

weaving.

The trading of wool and

cloth took place in public houses throughout the town

on market days. Local weavers produced a range of

woolen cloth including: kerseys, "a coarse

woolen cloth of light weight and often ribbed"; baizes,

"a coarse woolen stuff of plain colour with a nap on

one side, used for table covers"; and most

importantly, flannel, "a soft loosely woven

cloth". Most of the cloth woven in the Parish of

Rochdale went for export to Europe and the Americas.

If Manchester can be hailed as the place where "Cotton

was King", then Rochdale was the place where "Flannel

was King". Cotton didn't become the dominant textile

in Rochdale until 1830.

The change from a

hand-operated cottage-based industry to a

machine-operated factory-based industry brought great

wealth and a lot of misery to the area.

The first textile mills used water-power and in some

cases were converted corn mills located by the rivers

that rushed down off the surrounding hills. The first

chimney went up in Rochdale on Hanging Road in 1791 and

heralded a change to steam power. It was soon joined by

many others and the pollution of the air was only

surpassed by the squalor in which the growing population

lived.

The mechanization of the

woolen industry was slower than the "progress" seen in

cotton. Consequently, the way in which Rochdale

developed was somewhat different from some of its

neighbours to the south and to the north in the

Rossendale Valley.

As the farmer-weavers

upped stakes and moved into town, to take advantage of

the opportunities for trade weavers, cottages sprang

up around Rochdale. Master weavers built these three

storey buildings with a characteristic array of

windows on the top floor. The windows provided the

light required by journeymen weavers, employed on a

piecework basis, who operated the looms located on the

top floor.

The move

into town saw Rochdale grow from 14,000 in 1801 to

23,000 by 1821.

Chartism

The Struggle for Universal

Sufferage

During the early years

of the 19th century, when Rochdale was thriving as a

textile manufacturing centre, all was not peace and

harmony. At this time the inhabitants of the town and

surrounding area could be divided into three groups or

classes. There were the members of the upper-class,

the wealthy land owners, the Tory gentry, who were

members of the Anglican Church. These people had the

ability to wield real power through their connections

in the church, the magistrature, and by casting a vote

in elections. The middle-class, the nouveau-riche

entrepreneurs who were ambitious, self-made men, saw

themselves as the engines of this economic boom but

completely disenfranchised since they were unable to

vote in elections. Many of the members of this group

belonged to one or other of the diverse non-conformist

churches that had sprung up in the area, Politically,

they were Whigs and later Liberals and they were

determined to wrestle power away from the traditional

ruling class. At the bottom of the heap economically

and politically were the working-class who made up 96%

or the population of Rochdale.

The industrialization of

the textile industry led first to the concentration of

formerly rural people into Rochdale. The population

exploded and by 1841 there were 68,000 people in a

town that just 20 years earlier had 23,000. Living

conditions in the overcrowded, squalid and

increasingly polluted town were dreadful. As

mechanization increased and prices for cloth

fluctuated, the wages paid to factory workers and the

prices paid to independent handweaves spiraled ever

downwards. As local medical practitioners at the time

commented "the labouring classes in the Borough of

Rochdale......are now suffering great and increasing

privations. That they are unable in great numbers to

obtain wholesome food in sufficient quantities to keep

them in health; and that they are predisposed to

disease and rendered unable to resist its

attacks.....In this respect the population amongst

whom we practice are in a much worse state now than

they were five or six years ago."

It was in this climate

that Rochdale as a town developed, and the drama

played out in the meeting halls and on the streets of

the town over several decades. Driven by a thirst for

wealth and power the middle-class clashed on ideologal

grounds with the ruling upper-class Tories. Meanwhile,

the working-class fought to stave off starvation and

learned how to organize their considerable numbers

against the overwhelming power of the rich and

powerful who controlled every aspect of their lives.

The political battle

that ensued at the beginning of the 19th century was

no simple struggle. The often competing goals of the

various classes were inevitably intertwined. I will

endeavour to unravel them but apologize in advance for

any oversimplification.

In 1815 at the Battle of

Waterloo, Napoleon's army was defeated and the Twenty

Years War came to an end. Having won the war, England

faced a serious problem at home. In fact, the country

teetered on the brink of revolution. Even before the

war there had been unrest in the country . It was in

every respect a period of repression in which the

condition of the poor had steadily deteriorated.

Exploited in factories by the new capitalists and on

the land by the old aristocracy, the frustrations of

the poor often manifested themselves in violence,

notably bread riots in Rochdale. In 1791 a riot was

put down by the militia, on the order of magistrate

Thomas Drake, resulting in two deaths. Falling wages

precipitated attacks on weavers' cottages, and in one

incident in 1808, an angry crowd liberated several

men, who had been arrested, and burned down the

"lock-up" on Rope Street. In reaction to the unrest

Rochdale became a barracks town giving it a permanent

military presence ready at a moments notice to put

down any riots.

The move to reform the

existing parliamentary system dominated the political

mood of the country. A party of reform minded men,

equipped with blankets to keep them warm on overnight

stops, set off from Manchester on March 24, 1817 to

present a petition to the Prince Regent in what became

known as the March of the Blanketeers.

The same year a large

political reform meeting was held on Cronkeyshaw

Common outside Rochdale. 35,000 men and women marched

through Rochdale to the Common, and amongst the crowd

at the meeting was Samuel Bamford, a reformer/radical

from Middleton.

Two years later Bamford

led a party of Middleton people to an assembly on open

ground near St. Peter's Church in Manchester, where

they hoped to hear Henry "Orator" Hunt speak.

"They wore their Sunday

suits and clean neckties; and by the side of fustian

and corduroy walked the coloured prints and stuffs of

wives and sweethearts, who went as for a gala-day, to

break the dull monotony of their lives, and to serve

as a guarantee of peaceable intention. Such at least

was the main body, marshalled in Middleton by

stalwart, stout-hearted Samuel Bamford, which passed

in marching order, five abreast down Newton Lane,

through Oldham Street, skirted the Infirmary Gardens,

and proceeded along Moseley Street. each leader with a

sprig of peaceful laurel in his hat."

There is a memorial to Samuel NBamford in the

churchyard in Middleton, where he is buried.

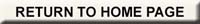

Among the throng on St.

Peter's Field it was reported that some banners were

seen saying "Bread or Blood", "Liberty or Death" and

"Equal Representation or Death". Hunt had barely made

it onto the stage when the 15th Hussars, dispatched by

magistrate the Rev. Hay, later the Vicar of Rochdale,

rode, with sabers drawn, into the crowd . Eleven

people were killed and 400 injured in what became

known as the Peterloo Massacre.

The government of the

day finally addressed the parliamentary reform issue

in 1832, by passing the Parliamentary Reform Act.

Unfortunately, for the majority of the people in

Rochdale and around the country nothing changed. The

Act abolished "Rotten Boroughs" and gave their seats

to new towns including Rochdale. It extended the

franchise but only on the basis of wealth to £10

householders in boroughs and £50 tenants in the

counties. In Rochdale this meant that 687 out of a

population of 28,000 could now vote.

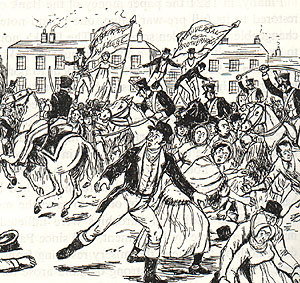

Rightly or wrongly, the

mass of the working-class saw the right to vote as a

chance to influence government policy (something that

continues to be almost impossible, even with universal

sufferage) and to improve their miserable lot. A

national movement known as Chartism grew up to address

this working-class discontent. It derived its name

from the six point charter that set out the demands of

the organization, demands which some were prepared to

back with force if necessary:

1. Universal (male) sufferage.

2. Annual Parliaments.

3. Vote by (secret) ballot.

4. Abolition of property qualifications for M.

P.'s.

5. Payment of M. P.'s.

6. Equal Electoral Districts.

In Rochdale one of the

prominent figures in the Chartist movement was Thomas

Livsey. Livsey was a local lad, the son of a

blacksmith, who was educated until the age of 15 in

Rochdale. Livsey also worked locally on such issues as

shortening working hours in the mills, restricting

child labour and fighting the Poor Laws that

introduced the despised workhouses. Livsey was an

affective interlocutor between the middle-class and

the working-class and a strong advocate for the

latter. He was also involved in the development of the

local Co-operative movement.

The struggle for

acceptance of the Charter raised passions and for a

while there were real concerns that it could lead to

an armed insurrection. Plans to organize a period of

sustained protest across the country in 1839 collapsed

in disarray. By 1842 when the Charter was still a

dream, it began to be apparent to a lot of people that

the way forward for working-class people lay not in

electoral reform but in self-improvement, a decision

which in Rochdale led to Co-operation.

The middle-class fought

for parliamentary reform because they wanted to have

access to the power that the Tory gentry had by right.

The only way to achieve the change they wanted was to

create a ground swell of discontent and to do this

they needed to enlist the support of the

working-class. The working-class joined the frey in a

desperate attempt to give some strength to their

demands for improved living and working conditions.

Throughout this whole period, life and work in

Rochdale was characterized by riots and strikes over

food shortages, pay and working conditions.

Labour Strife

The Struggle for a Living

Wage

There were a number of

contentious issues on the increasingly industrial

scene in Rochdale around which disagreements raged.

The first was the wage rate. After drawn-out

negotiations a complicated system of payments was

agreed in Rochdale. Known as the Statement Price it

was settled in 1824. However, from that point on,

wages entered a downward spiral that sparked-off a

series of strikes and other labour actions.

Another highly

contentious issue was the practice of some employers

to pay their workers in kind. Using what were known

as Truck Shops workers took their pay in food and

goods. The goods were expensive meaning that the

worker saw very little return for his or her sweat.

Worse than that, they were often rotten or

adulterated, with chalk added to the cheese, white

sand in the sugar and mud in the coffee.

There was, of course,

the problem of mechanization. The replacement of

workers by machines was a major issue in 19th

century Rochdale, and continues to affect

management-worker relationships around the world to

the present day. Rochdale, with its emphasis on wool

rather than cotton, was somewhat slower to introduce

highly mechanized production and relied for much

longer than other Lancashire textile towns on

hand-weaving, for instance. The new machinery became

the target of attacks from frustrated hand-weavers

who saw the price they were being paid fall

dramatically.

Rochdale weavers

fought an ongoing battle during the early decades of

the 19th century just to hold on to what they had,

in terms of living and working conditions, and to

stave-off the efforts of their employers to

introduce changes which eroded them.

From 1801 until 1824

it was illegal for workers to form trade unions. In

1824 the weavers and spinners in Rochdale, both men

and women, formed the Rochdale Journeyman Weavers'

Association.

It wasn't long after

the Association was formed that the attacks on the

Statement Price began. Over the coming years the

workers employed various strategies to combat their

employers. When two mill owners began to undercut

both wages and prices, the workers convinced twelve

other employers to stand with them. The dissenting

mills actually took on the workers who struck the

two undercutting mills. In the end, the workers

earned a reinstatement of the rate and forced the

two mill owners to contribute to the union's strike

fund.

Forcing divisions

between employers came to a swift end and, in fact,

the mill owners began to forge their own alliances.

The union countered this by seeking the financial

support of Rochdale's retail traders. To achieve

this they made it quite clear that to not support

the union would result in a boycott of the offending

business.

The union assiduously

denied its part in the workers' action against mills

that were introducing mechanization. In May of 1829

twenty workers, involved in an attack on a mill,

were arrested. A mob attacked the Rochdale jail

where they were being held. Ten people died when the

troops guarding the jail opened fire.

By 1830 wages in

Rochdale were about 40% below the 1824 rate and a

general strike broke out involving six to seven

thousand workers. In June of that year John Doherty,

of the National Association for the Protection of

Labour, made an appearance in town. His address was

so convincing that the spinners and weavers voted

unanimously to join his national union. However, the

promised advantages of belonging to a powerful

national association soon proved to be unfounded.

When it became clear that Doherty's words were not

backed by effective action, and when it was revealed

that the Rochdale subscriptions to the union had

been embezzled, the association came to an end.

Things were to get

worse. By the time the dreadful winter of 1841 hit,

the Rochdale workers were trying to cope on

one-third of the average wage for working people.

Strikes broke out again in August of 1842. Strikers

moved in groups from town to town bringing

production to a standstill by pulling the plugs on

the steam boilers in the mills. They became known as

"Plug Dragoons". In the end, though, starvation

forced the strikers back to work.

Co-operation

It would be reasonable

to ask how, out of all this chaos, mistrust, ill

treatment and double-dealing, Rochdale could be

regarded as the home of Co-opertion. The fact is

that it was this very chaos which stimulated some

people in Rochdale to look for a different way. It

had become clear to working people in Rochdale and

their enlightened supporters among the middle-class

that, if things were going to get better, they could

not expect help from either the government or their

capitalist employers. The government was resisting

all efforts towards universal sufferage and the

capitalists were insulating themselves against the

boom and bust nature of the marketplace by squeezing

their workforces. The way forward for working people

lay in self-improvement. The workers needed to build

associations that would provide them with education

and improved living conditions.

Robert Owen was born

in 1771 in Newtown in Wales. At the age of 16 he

moved to Manchester to take up a position with a

wholesale and retail drapery business. Owen was a

fast mover. At the age of 19 he borrowed £100 to set

up a company to manufacture spinning mules. Two

years later he moved on to become manager of

Drinkwater's large spinning factory in Manchester.

Exercising the 18th century equivalent of

"networking", he got to know David Dale the owner of

the Chorton Twist Company in New Lanark, Scotland,

at the time Britain's largest cotton spinning

business. The two men became good friends and in

1799 Owen married Dale's daughter. With financial

assistance from other Manchester business men, Owen

paid Dale £60,000 for his four textile mills in New

Lanark.

Here is where Owen's

reputation as a social engineer began. He was of the

opinion that all people were basically good and that

the more negative aspects of their behaviour were

forced upon them by the difficulties they faced in

life. He believed that in the right environment

people would be rational, good, and humane. He also

saw education as a vital part of this process. In

his New Lanark mills he changed the practice of

children as young as 5 working 16 hours days. He

introduced a minimum age of 10 and provided nursery

and infant schools for the under 10s. He also

provided a secondary school for his older child

employees. He banned physical punishment in the

mills and the schools.

Owen travelled the

country talking about his ideas, wrote books and

even sent his proposals on factory reform to

Parliament. He advocated the setting up of new

communities, which he called "Villages of

Co-operation". He believed that in time such a

movement would eliminate capitalism and replace it

with a "Co-operative Commonwealth".

Robert Owen was a very

influential figure in a Britain in which

trade-unionism and Co-operative movements were

developing. However, his wasn't the only voice. Dr.

William King of Brighton was a Co-operator but his

views were somewhat different from Owen's. He saw a

Co-operative store as central to a process that

would provide the working-class with an opportunity

to help themselves. He was proposing a shop that

would sell a limited number of products to members

of a co-operative. As profits provided capital, it

would be used to subsidize production of products by

members. Eventually, this would lead to the

establishment of factories and hence Owen's

Co-operative Commonwealth.

In 1832 the weavers

founded the Rochdale Friendly Co-operative Society

and in 1833, inspired by the enthusiasm for Owen's

ideas, they actually opened their own shop at 15

Toad Lane. This first shop only lasted two years

before it was forced to close.

In 1844 the Rochdale economy was in another of those

dizzying nose-dives that once again led to wage

reductions which in turn triggered strikes.

Unemployed weavers meeting at the Socialist

Institute and no doubt debating Chartist and Owenism

philosophies established a new society.

These Rochdale Pioneers

formulated the Rochdale Principles upon which their

version of co-operation were founded. These

principles were:

1.

Democratic control, one member one vote and equality

of the sexes

2. Open membership.

3. A fixed rate of interest payable on investment.

4.

Pure, unadulterated goods with full weights and

measures given.

5. No credit.

6. Profits to be divided pro-rata on the amount of

purchase made (the divi).

7. A fixed percentage of profits to be devoted to

educational purposes.

8. Political and religious neutrality.

With money raised from

the original 28 subscribers, a shop was founded in a

warehouse at 31 Toad Lane and it was equipped and

stocked. The shop opened on the 21st of December,

1844. By 1848 the Co-operative had 140 members.

However, when the Rochdale Savings Bank collapsed in

1849, due to the fact that one of its underwriting

mill owners George Howarth had embezzled the funds

to prop up his own failing business, people turned

to the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society so that

their money would be in safe hands. The society's

membership went up to 390 that year, but by 1860 it

had sky-rocketed to 3,500.

The Rochdale style of

consumer Co-operative became the norm and the model

for others to follow. The principles were applied in

neighbouring towns and then across the country. By

1880 the national membership of consumer societies

had reached over a half a million people and by the

turn of the century 1.5 million.