|

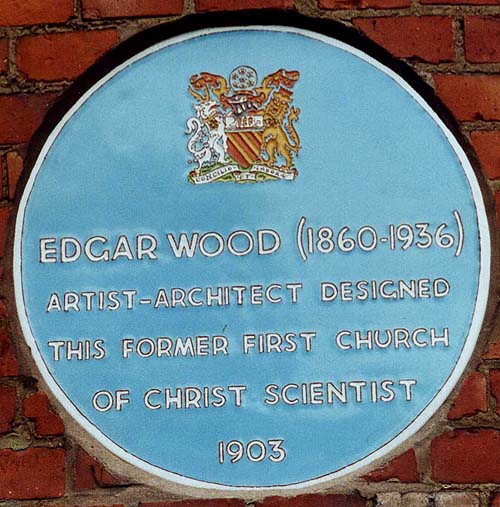

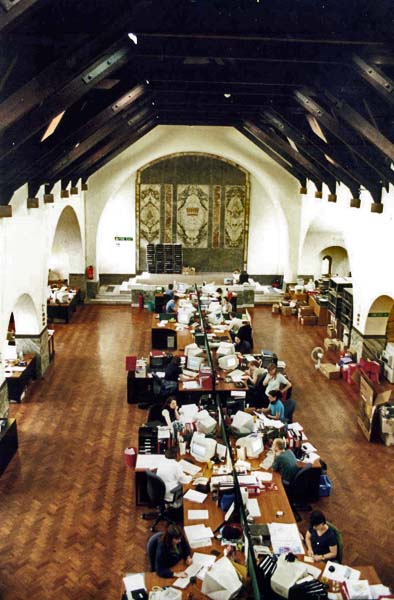

1903  What follows are notes on Edgar Wood and the First Church of Christ, Scientist written by John H. G. Archer, School of Architecture, University of Manchester The Edgar Wood Centre is named to honour its architect, and this recognition indicated that the building and its author have an unusual place in Manchester's architectural life. It is the only major work by Wood in the city, and despite suffering some irreparable losses it still captures the imagination. The building now commemorating Wood was commissioned in 1902 as the First Church of Christ, Scientist. It was the first purpose-built church in Britain for Christian Scientists and the second in Europe. This left Wood relatively free from precedent. The requirements were simple: a main space was needed for worship and a subsidiary one as a reading room for the study of the scriptures and the works of Mary Baker Eddy. Christian Scientists were newly established in Manchester but were progressing rapidly under the leadership of a striking and dynamic woman, Lady Victoria Alexandrina Murry, a daughter of the Earl and Countess of Dunmore and a godchild of Queen Victoria. When it was decided to build, the church obtained a site on Daisy Bank Road and engaged Wood as architect. He had only recently finished a large and unusually handsome Wesleyan Church in Middleton, the Long Street Church (1899-1901). He was still in his prime and was both well established and successful, but he was still exploring and developing architecturally. This is reflected in the First Church as he modified and enriched the design over five years.  A

number of design drawings of the church are deposited

in the British Architectural Library, and with these

and a few others that have survived from Wood's office

it is possible to see how the design evolved. Wood

began with a sketch that is reminiscent of the Long

Street building, in which the church and school are

grouped around three sides of a courtyard that is

closed on the fourth side by a screen that gives the

sense of quiet and seclusion from the busy main road

on to which it faces. This was ideal for the Middleton

church but quite impractical for the First Church with

its far more limited accommodation. It shows only that

Wood was again seeking a space-enclosing plan form.

Free from the conventional liturgical associations and

needing an interior space that was primarily auditory,

Wood next designed an octagonal church crowned with a

pitched roof. In this the secondary functions, a

reading room and cloakrooms, respectively, are located

in two wings that project towards the front, and

between these is a central entrance vestibule with an

exceptionally tall steeply-pitched gable with walls

that echo the geometry of the octagon. Wood developed

this scheme sufficiently to exhibit a drawing of it at

the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of 1903. By then,

however, it was superseded. Early in March he was

instructed that expenditure was to be limited to

£1500, and by the end of that month new plans had been

submitted and adopted. A rectangular hall was substituted for the octagon, and although this necessitated buying more land because of the greater length of the building, it had the advantage of permitting the work to be carried out in stages. The first contract included the construction of the vestibule, three bays of the six planned for the church hall, and a circular stair-turret located in the internal angle and serving a gallery: the wings were excluded. This first stage opened on 20th April 1904, and almost immediately the construction of the wings was commenced. By the spring of 1905 the entire front section of the church, including the light gate, paving and gardens had been completed at a cost of approximately £3,350.  The projecting arms, surviving from the octagon scheme, provide the enclosure that Wood had first set out to capture. It is strengthened by a reduction of the angle between the wings and dramatised by a tall prow-like white gable; it is still powerfully effective. A fine drawing of the church and forecourt was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1904 and subsequently it was published in the architectural press.  About eighteen months later, in the autumn of 1905, Wood was asked to complete the church by adding vestries and a board room. He included these in a wing that projects from the back of the church and at right angles to the main axis. One room, the former Board Room, is fitted with a notably handsome fireplace in green tiles and marble.  The extension of the church continues the line of the hall, built with a lofty, open, truss roof, but these was a considerable change because two shallow transepts and a short rectangular apse were added. The additions are structurally radical but visually harmonious. The nave is designed with aisles divided from the central space by semi-circular arcaded walls. At the transepts the arcade arches are simply enlarged to span the wider apse and the roof trusses continue above them without variation. The apse also is spanned by a semi-circular arch, maintaining this strong architectural theme, a surviving idea from the earliest sketch scheme based on the courtyard. The roofs of the three additional adjuncts are vaults constructed in reinforced concrete, a new material with which Wood was then experimenting having taken into his office as independent associate James Henry Sellers (1861-1954), with whom he shared many ideas and from whom he gained an insight into this new structural technique. It is used also in the form of a flat roof on the wing of vestries. Finally completing this stage, a porch was added to provide an entrance to the west trancept. It is massively built in carefully modeled brickwork and is domed internally in concrete. Its weighty character is classical and sculptural.  With

the main structure complete, by 1907 the church found

itself responsible for an unusual and architecturally

powerful building. The exterior, dramatic and

challenging with its massive gable and canted walls,

contains an interior that is tranquil and reposeful

with its quiet rhythm of arches, simple, plain colour,

natural materials, including a delicate green marble,

and the complete absence of any superfluous

decoration. Richly coloured stained-glass windows

depicting the healing miracles and designed by

Benjamin Nelson gave enrichment. Two other major

features of brilliant design distinguish the interior;

a reredos panel in quartered marbles, the centre-piece

containing in bas-relief the Christian Science emblem

of a cross and crown (a motif that may derive from the

Quaker William Penn's phrase 'No cross, no crown');

and in contrast, at the opposite end of the church

above the main entrance, an organ screen in the form

of a mushrabiyyah, and Arabic device of an open screen

inserted into window openings to admit light and air

but to preserve privacy. The screen here consists of

small panels and decorative frets of chevrons,

connected by rods decorated by beads and bobbins.

Patterned and painted in dark green, white, gilt and

flashes of brilliant red, its simplicity and

complexity are fused in consummate artistry. These two

visual focal points on the main axis of the building

were linked by decorative inscriptions running the

length of the church, simple texts in a fine type-face

that carried the eye to the two great features of the

interior. For

over sixty years after its completion the church was

kept in immaculate order, virtually exactly as

designed by Wood. It was admired by many groups of

visitors and especially British, American and German

architectural historians. One of the latter (Dr.

Wolfgang Pehnt) considered it "a true piece of

Expressionism ante festum", and Sir Nikolaus Pevsner

described it as "one of the most original buildings of

1903 in England or indeed anywhere" (B.O.E.S. Lancs,.

1969, p. 322). Social changes and a residential exodus

left it impoverished and vulnerable. On 26 December

1971 the church closed without prior notice. Vandals

immediately broke in and commenced a systematic

looting of all convertible metal. After a period when

its fate hung in the balance the church was bought by

Manchester Corporation and has now been repaired and

restored successfully under the direction of the City

Architect. Much was lost but some fittings and

furniture have been saved. The relics of the stained

glass are now in the Whitworth Gallery, and the

church's ceremonial chairs from the rostrum have been

placed there also. Another fine piece of furniture, a

library display cabinet designed by J.H. Sellers, has

been given to the John Rylands University Library. The

building itself has become an acquisition in which the

city rightly takes pride. The

Edgar Wood Centre is a fine example of an architecture

free from historicism, created when architects were

seeking individual solutions to the problem of style

that bedeviled Victorian architects. Wood's response

in this widely eclectic building is poetry and

artistic. In its pursuit of expression is defies

rationalism but remains hauntingly memorable. It is

not uncharacteristically Mancunian, but Manchester

rose to the occasion in its conservation. Everyone has

something to learn here, and Manchester would be an

immeasurably poorer city without this building's

inspiration and brilliance.

******************************

Over the years the building has seen a number of changes. It started life as a place of worship but when it closed as a church it fell into disrepair. Over the years it was victim to vandals, but was eventually restored to its former glory by the City of Manchester and in the 1980s was used by the City of Manchester College of Higher Education as a drama and music facility and named The Edgar Wood Centre. When I first visited the building it was occupied by a company that produced training videos. Today it is once again a church belonging to the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God.

|