|

The Hulme Crescents

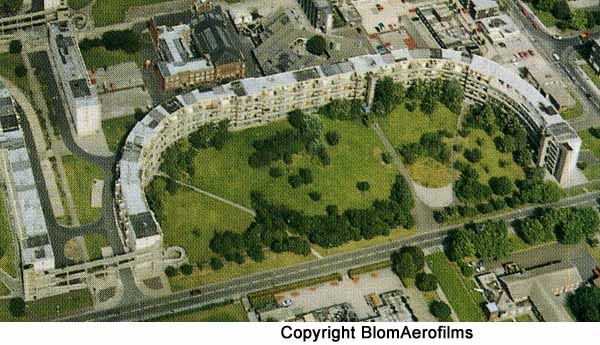

The image above is shown with the generous permission of BlomAerofilms

The Hulme Crescents

dominated the skyline of Hulme for nearly two

decades beginning in 1972. In their day they

were one of the largest housing complexes of their

kind in Europe. However, the Crescents are no

more and, to understand why they were built and why

they were demolished soon after, you need to know

something of the history of the area and of fashions

in housing architecture at that time.

*********************

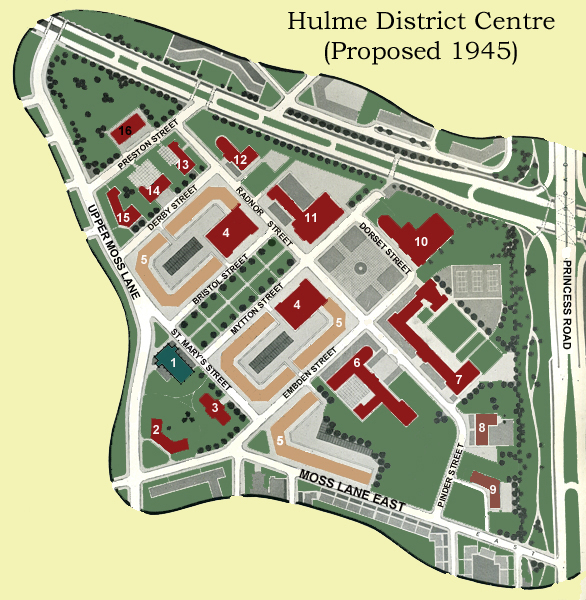

In 1945 the City of Manchester produced a plan for the reconstruction and development of the city. Among the many issues dealt with in that plan was the question of how the city was going to address the housing needs of its citizens. The 1945 plan said this about the state of housing in the city: “In many respects the Manchester citizen of 1650 was in a better position to enjoy a healthy life than the present-day inhabitant of Ancoats, Beswick or Hulme. If the quality of his house was poor, and the sanitary arrangements primitive or non-existent, at least he had a fairly large strip of garden and the open country was only a few minutes’ walk away. Today about 60 per cent of Manchester’s houses are built at densities in excess of 24 to the acre. Most of these 120,000 houses are old and must in any event be rebuilt in the comparatively near future. Over 60,000 are considered by the Medical Officer of Health to be unfit for human habitation.” The plan described the existing housing stock in areas like Hulme as, “Endless rows of grimy houses: no gardens, no parks, no community buildings, no hope.”  (Note: The image above is not of Hulme but is characteristic of the housing described in the 1945 Plan) The Plan called for the construction of new communities on the fringes of the city and the reconstruction of existing communities to provide the air and light that people needed and the green spaces, shopping and community centres that would make their lives better. The drawing below

shows the vision for Hulme's District

Centre. It was never implemented.

However, over the next two decades the city encountered one problem after another in trying to implement its plans. Attempts to build on the Cheshire fringes were opposed and abandoned, and although many people moved out of the inner city into Wythenshawe and Hattersley, it was clear that the solution would have to include clearing the existing housing stock and rebuilding. Manchester like other cities had turned to high-rise flats as a solution and had, in the 1950s and 60s, adopted many of the pre-fabricated building systems that were popular at the time.  Above: The Fort Ardwick Estate However by 1967 the Manchester Housing Committee was of the opinion that, “dwellings must not be put into ‘office block’ arrangements.” The statement went on to say that they, “foresaw no building higher than a six-storey maisonette.” A year later the 23 storey Ronan Point Flats in London collapsed, “like a pack of cards”, killing 5 people and injuring 80 and that event threw a huge shadow over the tower block as a housing solution. *****************

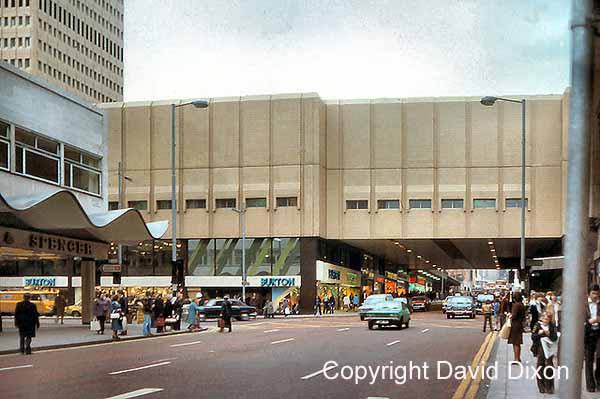

So what happened next in Hulme was the collision of the need for a housing solution with the advent of a new style of civic building and the arrival in Manchester of the architectural partnership of Hugh Wilson and J. Lewis Womersley. Wilson had been the Chief Architect for the new town of Cumbernauld in Scotland. The original plan for Cumbernauld was for a new town capable of accommodating 50,000 to 80,000 people. Wilson assembled a group of planners and designers from around the world who saw this as an adventure in urban planning. Their plan called for, “a single multi-purpose town centre surrounded by high-density neighbourhoods. The neighbourhoods would not have their own retail centres, but would instead be connected to the main centre by pedestrian footpaths. Residents would be able to walk safely to and from the centre without ever coming across a car: a giant motorway system catered for those who wanted to drive through the town or to the centre.” What they created has been described by some as, “A soulless concrete carbuncle surrounded by roundabouts.” It is important to say that not everyone shares this view but it is relevant in relation to what happened in Hulme. J. Lewis Womersley was the Chief Architect for the City of Sheffield in the 1950s. He hired Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith to design the infamous Park Hill Flats. This huge complex was designed to replace the Park Hill slums and rehouse its residents in “Streets in the Sky”. Work began in 1957 and the walkways that provided access within and between the blocks were so wide that a milk float could still deliver to the doors of the residents. However, the paradise that was envisaged did not materialize and Park Hill became known as San Quentin reflecting the state of decay and crime that pervaded it. Park Hill still stands and after gaining listed status it is undergoing, somewhat controversially, a restoration/reconstruction by Urban Splash under the supervision of English Heritage. Wilson and Womersley arrived in Manchester in the 1960s when the Victoria University of Manchester and the City Council commissioned them to draw up a plan for the development of the university and hospital quarter. As part of this project they designed the Precinct Centre on Booth Street.  In 1972 work began

on the Arndale Shopping Centre which they

designed.

The image above is shown here with the generous permission of David Dixon In 1965 Wilson

& Womersley had submitted a plan for a £4

Million redevelopment of Hulme which as John J.

Parkinson-Bailey explains in “Manchester - An

Architectural History” involved:

“thirteen tower blocks; low-rise concrete

blocks clad in a variety of materials, and

connected together by aerial walkways; and the

crescents - four long, curved, south facing

blocks of flats and maisonettes connected by

walkways and bridges.” The

Crescents sat astride Stretford Road which had

once been a vibrant shopping corridor. By

1972 “over 5,000 new houses

had been built in less than eight years and

over 3,000 of these were deck access.”

Wilson and

Womersley believed that their design for the

Crescents would see the recreation in Hulme of the

grand crescents of London and Bath and to

reinforce this they named them after the

architects Adam, Nash, Barry and Kent.

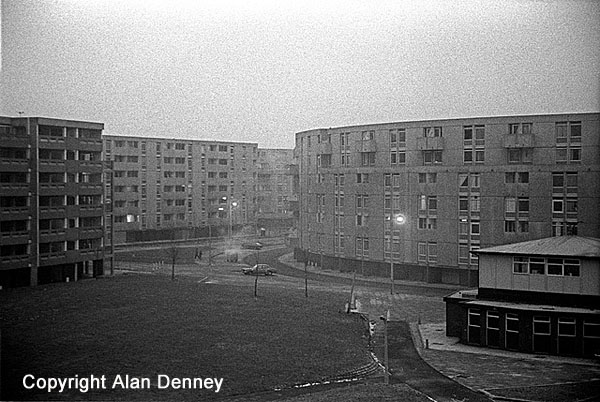

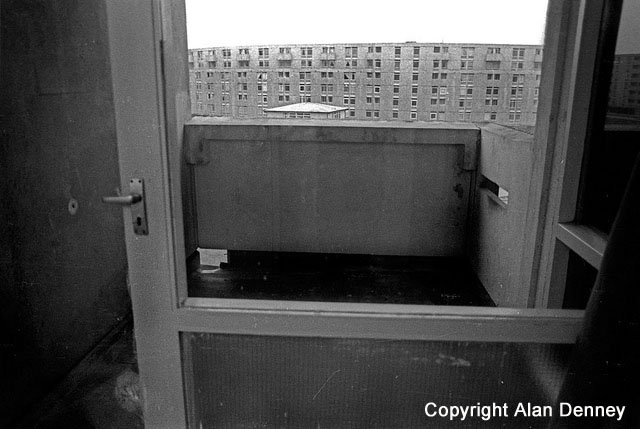

The four black &

white images below of the Hulme Crescents are shown

here with the generous permission of Alan

Denney

However, it didn’t

take very long for things to go wrong. Shoddy

construction resulted in the Crescents

leaking. The underfloor heating system proved

to be expensive to use and the leaking problem

combined with inadequate heating resulted in

extensive condensation problems.

The buildings were

infested by cockroaches and mice that found the

ducting for water and wiring their own “streets in

the sky”. Three years after they had moved in,

96.3 per cent of the residents wanted to

leave. The lifts rarely worked and vandalism

and indifference saw the Crescents become unsanitary

and unkempt. The walkways provided perfect

venues for crime and ideal escape routes for

criminals. Residents found themselves hostages

in their own homes.

Less than 20 years

after they had been built, the Crescents were

demolished as a first step in a complete rethink of

Hulme as a community.

|