The October 1973

edition of the Arup Journal included a

reprinting of a paper by Ove Arup and Jack

Zunz that was first published in the

Structural Engineer, March 1969. They

began by saying that, "... The

difficulty with writing anything about the

Sydney Opera House is to know where to

begin, what to include and where to end.

There is something for everybody - it is

all things to all men. It is a dream that

never was, a structure that could barely

be built, an architectural tour de force,

a politician's nightmare, a population's

talking point and much more. It is not so

much a building as a controversy.”

The origins of the Sydney Opera House can be

traced back to the 1940s when Eugene Goosens

first proposed the construction of a concert

hall capable of hosting opera

productions. This apparently was the

beginning of a whole history of confusions

surrounding the project because the idea was

to create what today we would call an arts

centre, a multi-functional venue, but the name

Opera House has stuck despite the fact that it

is only one aspect of its life. A decade

later a site was chosen. Bennelong Point

had been home to Sydney’s tram sheds but it

was regarded as a perfect site for a landmark

building, projecting out into Sydney Harbour

adjacent to the Harbour Bridge.

The

copyright holder

of this file allows anyone to use it

for any purpose, provided that the

photographer is credited.

The

image was added to Wikipedia by

Rodney Haywood. For more

details click on the image.

It was posted

on Wikimedia by Knodelbaum. The

full details of the license can be seen

by clicking on the image.

An international competition was launched for

the design of a building capable of providing

facilities for the musical and dramatic

arts. At the heart of the commission was

the requirement for two main performance

halls. The larger of the two capable of

accommodating audiences of between 3000 and

3500. The smaller with approximately

1200 seats. The design of the Danish

architect Jørn Oberg Utzon was chosen from the

200 entries. At the time, and perhaps a

prediction of problems ahead, the adjudicators

said of Utzon’s design that the drawings

submitted were, “... simple to the

point of being diagrammatic.

Nevertheless we have returned again and

again to the study of these drawings and

we are convinced that they present a

concept of an opera house which is capable

of becoming one of the schemes to be the

most creative and original submission.

Because of its very originality it is

clearly a controversial design. We are,

however, absolutely convinced about its

merits .. ."

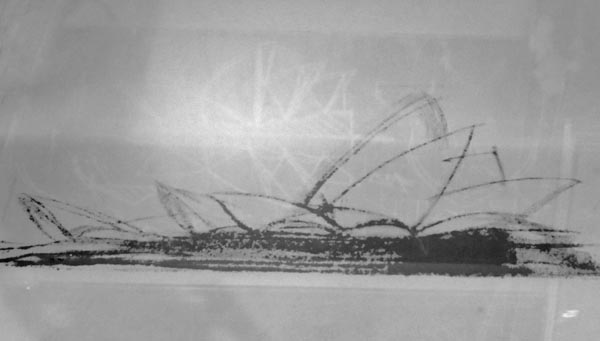

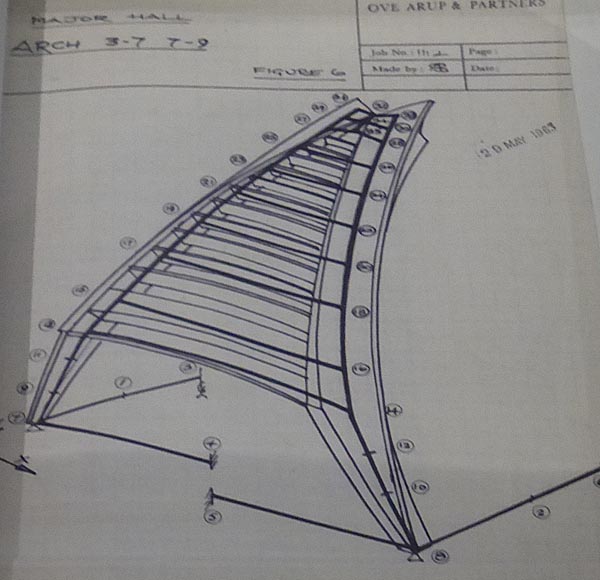

The item above was an exhibit in

the "Arup - Engineering the World" at

the Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

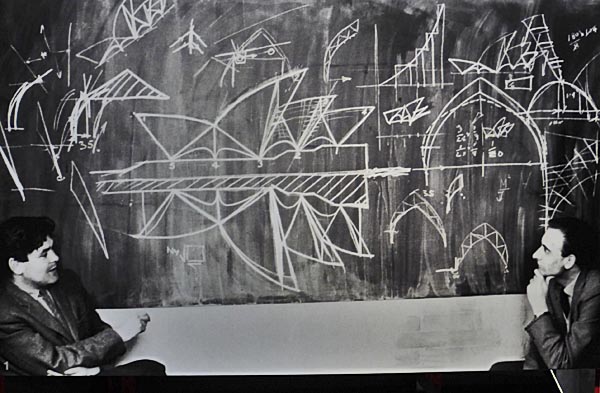

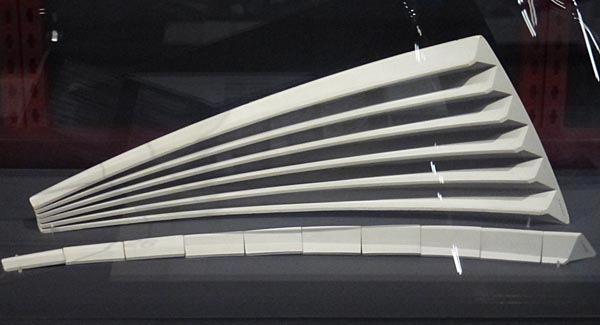

The item above was an exhibit in

the "Arup - Engineering the World" at

the Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

“Utzon conceived

the scheme which he submitted for the

competition apparently unaided by

structural engineering advice. The

distinctive sculptural quality of the

building with its roof structure,

often likened to billowing sails, was

an essential part of his first

proposals. On the other hand the

design was extremely sketchy and no

more than an indication of the

architect's intentions. The shape of

the roof was based on an intuitive

technical assessment of how to create

surfaces with a very strong aesthetic

appeal. All surfaces were free

shapes without geometric definition

and their structural viability had to

be proved. Strictly speaking. Utzon's

intuitive technical assessment turned

out to be erroneous. He had visualized

the roof as thin shells. This was not

possible since the very

shape of the roof introduced high

bending moments regardless of any

structural system.”

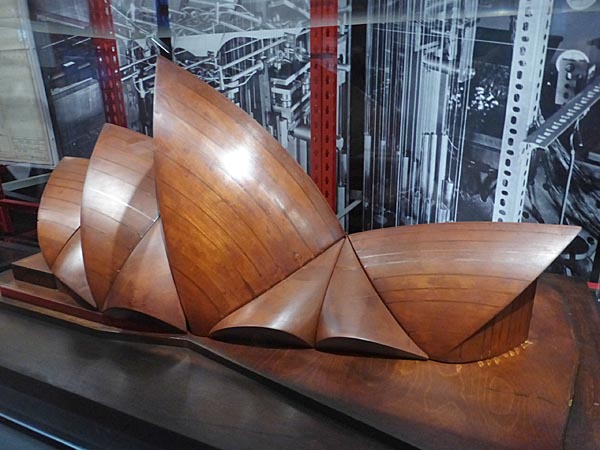

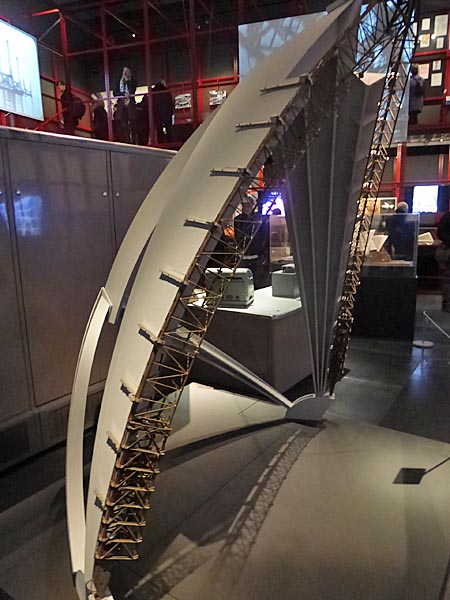

The item above was an exhibit

in the "Arup - Engineering the

World" at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

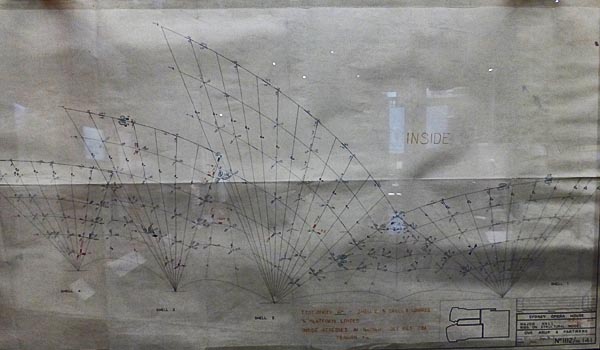

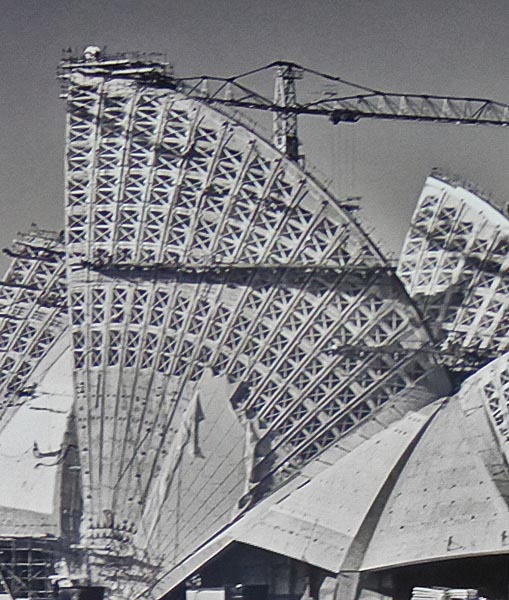

The item above was an exhibit

in the "Arup - Engineering the

World" at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

Many of the designs

submitted during the competition phase

proposed that the two halls be

arranged back to back with a shared

fly-tower in the centre, Utzon

regarded this concept as inappropriate

since it would require two entrances

at either end of the building which

would be difficult to achieve on a

peninsular site. His design put

the halls side by side which in itself

posed challenges because the stages no

longed had easy access from the sides

and other systems needed to be

developed for moving on and off the

stage.

The site posed other problems.

It was composed of fill deposited

within a sea wall. Water freely

percolated through the silt.

Beneath is a bedrock of Hawkesbury

sandstone that is heavily faulted and

interlaced with clay

seams. The foundation for

the building required 700 bored piers

as well as reinforced concrete

foundations on top of strip and pad

concrete footings.

The politicians'

nightmares referred to above, came in

the form of a project that was

expected to take 5 years and took 15

and in a cost overrun from the

projected $3.5M to $102M. The

inevitable tensions led to a

confrontation between representatives

of the New South Wales Government and

the architect and in March of 1966

Utzon went home to Denmark never to

return. He was replaced by a

team made up of Peter Hall, Lionel

Todd and David Littlemore. Over the

next 10 years they along with Arup

overcame what must have seemed like

unfathomable problems to bring Utzun’s

vision to fruition.

The most visible of the challenges was

the construction of the roof.

The Opera House website says that, "...

“The design solution and

construction of the shell

structure took eight years to

complete and the development of

the special ceramic tiles for the

shells took over three

years. The project was not

helped by the changes to the

brief. Construction of the

shells was one of the most

difficult

engineering tasks ever

to be attempted. The revolutionary

concept demanded equally

revolutionary engineering and

building techniques. Baulderstone

Hornibrook (then Hornibrook Group)

constructed the roof shells and

the interior structure and fitout.

“

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

Although the

finished shells look like the

billowing sails of ships, they

disguise the fact that they are in

fact made up of a series of concrete

ribs arranged in a fan-like

structure. Arup explain that, "...

The roof structure covers the two

main halls and the restaurant.

There are three main elements

forming each roof structure

- main shells, side shells, and

louvre shells. ...

Each of these shells is made up of

two half-shells, symmetrical about

the central axis of the hall. Each

half is a reflection of the other,

mirrored about the vertical plane

of the hall axis.

..... Each half main shell

consists of a series of concrete

ribs. The centre-line of each rib

is a great circle of the sphere.

Centre-lines are equally spaced

(3.65° apart) throughout each main

shell, each centre-line passing

through the pole of the sphere. In

this way ribs radiate from the

podium and they become wider up

the shell, successive ribs

becoming longer or shorter as the

case may be.”

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

The item

above was an exhibit in the

"Arup - Engineering the World"

at the Victoria & Albert

Museum, London Nov 2016

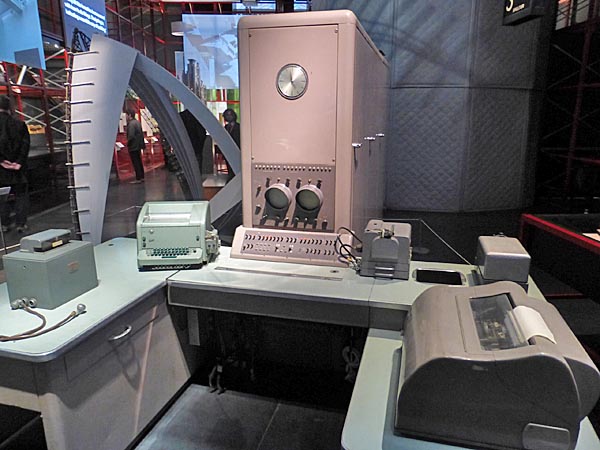

Arup used a computer

to assist with their engineering

work.

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World" at the

Victoria & Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

In 2007 the

Opera House was added to UNESCO’s

list of World Heritage sites

describing it as, “... a

great architectural work of

the 20th century. It

represents multiple strands of

creativity, both in

architectural form and

structural design, a great

urban sculpture carefully set

in a remarkable waterscape and

a world famous iconic

building.” The

Opera House website adds that it

is, “... a masterpiece of

late modern architecture. ...

The

item above was an

exhibit in the "Arup -

Engineering the World"

at the Victoria &

Albert Museum,

London Nov 2016

The images above and below are

shown here under the Creative Commons

Attribution-Share

Alike 3.0 Unported

license.

It

was posted on Wikimedia by

Knodelbaum.

... It is

admired internationally and

proudly treasured by the

people of Australia. It was

created by a young architect

who understood and recognised

the potential provided by the

site against the stunning

backdrop of Sydney

Harbour. Denmark’s Jørn

Utzon gave Australia a

challenging, graceful piece of

urban sculpture in patterned

tiles, glistening in the

sunlight and invitingly aglow

at night."

Updating the story of the building

the website for the Opera House

says that, "... In 1999,

Jørn Utzon was re-engaged as

Sydney Opera House architect

to develop a set of design

principles to act as a guide

for all future changes to the

building. These

principles reflect his

original vision and help to

ensure that the building’s

architectural integrity is

maintained. .... Utzon's first

major project was the

refurbishment of the Reception

Hall into a stunning, light

filled space which highlights

the original concrete 'beams'

and a wall-length tapestry

designed by him which hangs

opposite the harbour

outlook. Noted for its

excellent acoustics, it is the

only authentic Utzon-designed

space at Sydney Opera House

and was renamed the Utzon Room

in his honour in 2004."

The year before Utzon had been

awarded the prestigious Pritzker

Prize, international

architecture's highest

honour. Jørn Utzon died on

November 29, 2008, in Helsingør,

Denmark

|