|

First Church of Christ Scientist Without question, one of the real gems in Victoria Park was and is, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, known, in honour of its architect, as The Edgar Wood Centre. Edgar Wood designed it in a style influenced by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. The building fell into disrepair over the years and fell victim to vandals, but in recent years it was restored to its former glory by the City of Manchester and in the 1980s was being used by the City of Manchester College of Higher Education as a drama and music centre.

|

|

|

What follows are notes on Edgar Wood and the First Church of Christ, Scientist written by John H.G. Archer, School of Architecture, University of Manchester

Edgar Wood (1860-1935) practised from Manchester about the turn of the century and gained a considerable reputation both in Britain and abroad, notably in Germany. British design was then of European significance. His work is principally domestic, but he designed several churches and small commercial buildings. He worked as an individual designer, mostly with only one assistant, and confined himself to the smaller type of building that he could control personally. Although he was active in Manchester for over twenty years, most of his work is in nearby towns, such as Rochdale, Oldham and Middleton (of which he was native), and in outlying districts such as Bramhall and Hale. He contributed to Manchester in various ways. He was a founder of the Northern Art Workers' Guild in 1896, one of the major provincial societies within the Arts and Crafts Movement; he was president of the Manchester Society of Architects from 1911-12; and he was instrumental in saving the colonnade of Manchester's first town hall, designed by Francis Goodwin, which stood in King Street and was demolished c. 1911. Wood raised a public appeal and prepared a scheme for the re-erection of the colonnade in Platt Fields park, and when this was rejected he drew up another for a site in Heaton Park where the colonnade now stands, a magnificent Ionic wide screen and a fine parkland feature.

A number of design drawings of the church are deposited in the British Architectural Library, and with these and a few others that have survived from Wood's office it is possible to see how the design evolved. Wood began with a sketch that is reminiscent of the Long Street building, in which the church and school are grouped around three sides of a courtyard that is closed on the fourth side by a screen that gives the sense of quiet and seclusion from the busy main road on to which it faces. This was ideal for the Middleton church but quite impractical for the First Church with its far more limited accommodation. It shows only that Wood was again seeking a space-enclosing plan form. Free from the conventional liturgical associations and needing an interior space that was primarily auditory, Wood next designed an octagonal church crowned with a pitched roof. In this the secondary functions, a reading room and cloakrooms, respectively, are located in two wings that project towards the front, and between these is a central entrance vestibule with an exceptionally tall steeply-pitched gable with walls that echo the geometry of the octagon. Wood developed this scheme sufficiently to exhibit a drawing of it at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of 1903. By then, however, it was superseded. Early in March he was instructed that expenditure was to be limited to £1500, and by the end of that month new plans had been submitted and adopted. A rectangular hall was substituted for the octagon, and although this necessitated buying more land because of the greater length of the building, it had the advantage of permitting the work to be carried out in stages. The first contract included the construction of the vestibule, three bays of the six planned for the church hall, and a circular stair-turret located in the internal angle and serving a gallery: the wings were excluded. This first stage opened on 20th April 1904, and almost immediately the construction of the wings was commenced. By the spring of 1905 the entire front section of the church, including the light gate, paving and gardens had been completed at a cost of approximately £3,350. The projecting arms, surviving from the octagon scheme, provide the enclosure that Wood had first set out to capture. It is strengthened by a reduction of the angle between the wings and dramatised by a tall prow-like white gable; it is still powerfully effective. A fine drawing of the church and forecourt was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1904 and subsequently it was published in the architectural press.

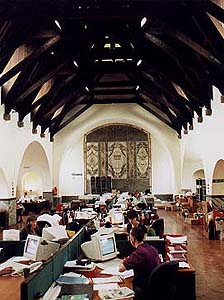

With the main structure complete, by 1907 the church found itself responsible for an unusual and architecturally powerful building. The exterior, dramatic and challenging with its massive gable and canted walls, contains an interior that is tranquil and reposeful with its quiet rhythm of arches, simple, plain colour, natural materials, including a delicate green marble, and the complete absence of any superfluous decoration. Richly coloured stained-glass windows depicting the healing miracles and designed by Benjamin Nelson gave enrichment. Two other major features of brilliant design distinguish the interior; a reredos panel in quartered marbles, the centre-piece containing in bas-relief the Christian Science emblem of a cross and crown (a motif that may derive from the Quaker William Penn's phrase 'No cross, no crown'); and in contrast, at the opposite end of the church above the main entrance, an organ screen in the form of a mushrabiyyah, and Arabic device of an open screen inserted into window openings to admit light and air but to preserve privacy. The screen here consists of small panels and decorative frets of chevrons, connected by rods decorated by beads and bobbins. Patterned and painted in dark green, white, gilt and flashes of brilliant red, its simplicity and complexity are fused in consummate artistry. These two visual focal points on the main axis of the building were linked by decorative inscriptions running the length of the church, simple texts in a fine type-face that carried the eye to the two great features of the interior. For over sixty years after its completion the church was kept in immaculate order, virtually exactly as designed by Wood. It was admired by many groups of visitors and especially British, American and German architectural historians. One of the latter (Dr. Wolfgang Pehnt) considered it "a true piece of Expressionism ante festum", and Sir Nikolaus Pevsner described it as "one of the most original buildings of 1903 in England or indeed anywhere" (B.O.E.S. Lancs,. 1969, p. 322). Social changes and a residential exodus left it impoverished and vulnerable. On 26 December 1971 the church closed without prior notice. Vandals immediately broke in and commenced a systematic looting of all convertible metal. After a period when its fate hung in the balance the church was bought by Manchester Corporation and has now been repaired and restored successfully under the direction of the City Architect. Much was lost but some fittings and furniture have been saved. The relics of the stained glass are now in the Whitworth Gallery, and the church's ceremonial chairs from the rostrum have been placed there also. Another fine piece of furniture, a library display cabinet designed by J.H. Sellers, has been given to the John Rylands University Library. The building itself has become an acquisition in which the city rightly takes pride. The Edgar Wood Centre is a fine example of an architecture free from historicism, created when architects were seeking individual solutions to the problem of style that bedeviled Victorian architects. Wood's response in this widely eclectic building is poetry and artistic. In its pursuit of expression is defies rationalism but remains hauntingly memorable. It is not uncharacteristically Mancunian, but Manchester rose to the occasion in its conservation. Everyone has something to learn here, and Manchester would be an immeasurably poorer city without this building's inspiration and brilliance. |

|

|

John H. G. Archer has written a number of works on Edgar Wood and is busy writing a new piece for publication. I am very grateful for his extremely interesting and informative notes on the architect and his remarkable building. One day I hope to see this building in person but John's description is so vivid I feel as though I already have. |

|

The building now commemorating Wood

was commissioned in 1902 as the First Church of Christ, Scientist.

It was the first purpose-built church in Britain for Christian

Scientists and the second in Europe. This left Wood relatively

free from precedent. The requirements were simple: a main space

was needed for worship and a subsidiary one as a reading room

for the study of the scriptures and the works of Mary Baker Eddy.

Christian Scientists were newly established in Manchester but

were progressing rapidly under the leadership of a striking and

dynamic woman, Lady Victoria Alexandrina Murry, a daughter of

the Earl and Countess of Dunmore and a godchild of Queen Victoria.

When it was decided to build, the church obtained a site on Daisy

Bank Road and engaged Wood as architect. He had only recently

finished a large and unusually handsome Wesleyan Church in Middleton,

the Long Street Church (1899-1901). He was still in his prime

and was both well established and successful, but he was still

exploring and developing architecturally. This is reflected in

the First Church as he modified and enriched the design over

five years.

The building now commemorating Wood

was commissioned in 1902 as the First Church of Christ, Scientist.

It was the first purpose-built church in Britain for Christian

Scientists and the second in Europe. This left Wood relatively

free from precedent. The requirements were simple: a main space

was needed for worship and a subsidiary one as a reading room

for the study of the scriptures and the works of Mary Baker Eddy.

Christian Scientists were newly established in Manchester but

were progressing rapidly under the leadership of a striking and

dynamic woman, Lady Victoria Alexandrina Murry, a daughter of

the Earl and Countess of Dunmore and a godchild of Queen Victoria.

When it was decided to build, the church obtained a site on Daisy

Bank Road and engaged Wood as architect. He had only recently

finished a large and unusually handsome Wesleyan Church in Middleton,

the Long Street Church (1899-1901). He was still in his prime

and was both well established and successful, but he was still

exploring and developing architecturally. This is reflected in

the First Church as he modified and enriched the design over

five years. About eighteen months later, in the autumn of 1905,

Wood was asked to complete the church by adding vestries and

a board room. He included these in a wing that projects from

the back of the church and at right angles to the main axis.

One room, the former Board Room, is fitted with a notably handsome

fireplace in green tiles and marble. The extension of the church

continues the line of the hall, built with a lofty, open, truss

roof, but these was a considerable change because two shallow

transepts and a short rectangular apse were added. The additions

are structurally radical but visually harmonious. The nave is

designed with aisles divided from the central space by semi-circular

arcaded walls. At the transepts the arcade arches are simply

enlarged to span the wider apse and the roof trusses continue

above them without variation. The apse also is spanned by a semi-circular

arch, maintaining this strong architectural theme, a surviving

idea from the earliest sketch scheme based on the courtyard.

The roofs of the three additional adjuncts are vaults constructed

in reinforced concrete, a new material with which Wood was then

experimenting having taken into his office as independent associate

James Henry Sellers (1861-1954), with whom he shared many ideas

and from whom he gained an insight into this new structural technique.

It is used also in the form of a flat roof on the wing of vestries.

Finally completing this stage, a porch was added to provide an

entrance to the west trancept. It is massively built in carefully

modeled brickwork and is domed internally in concrete. Its weighty

character is classical and sculptural.

About eighteen months later, in the autumn of 1905,

Wood was asked to complete the church by adding vestries and

a board room. He included these in a wing that projects from

the back of the church and at right angles to the main axis.

One room, the former Board Room, is fitted with a notably handsome

fireplace in green tiles and marble. The extension of the church

continues the line of the hall, built with a lofty, open, truss

roof, but these was a considerable change because two shallow

transepts and a short rectangular apse were added. The additions

are structurally radical but visually harmonious. The nave is

designed with aisles divided from the central space by semi-circular

arcaded walls. At the transepts the arcade arches are simply

enlarged to span the wider apse and the roof trusses continue

above them without variation. The apse also is spanned by a semi-circular

arch, maintaining this strong architectural theme, a surviving

idea from the earliest sketch scheme based on the courtyard.

The roofs of the three additional adjuncts are vaults constructed

in reinforced concrete, a new material with which Wood was then

experimenting having taken into his office as independent associate

James Henry Sellers (1861-1954), with whom he shared many ideas

and from whom he gained an insight into this new structural technique.

It is used also in the form of a flat roof on the wing of vestries.

Finally completing this stage, a porch was added to provide an

entrance to the west trancept. It is massively built in carefully

modeled brickwork and is domed internally in concrete. Its weighty

character is classical and sculptural.