|

The fact that Rochdale was a woolen town, in a time when cotton was dominating the textile industry in Lancashire, is ascribed to its proximity to Yorkshire. A huge impediment to this economic liaison though was the fact that in the early years trade was dependent on a transportation system that employed pack-horses trudging over treacherous pathways through the formidable hills.

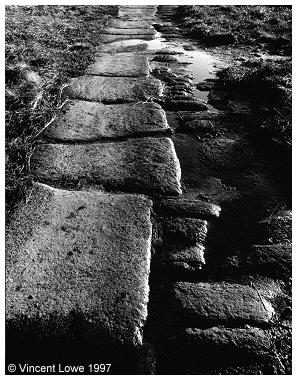

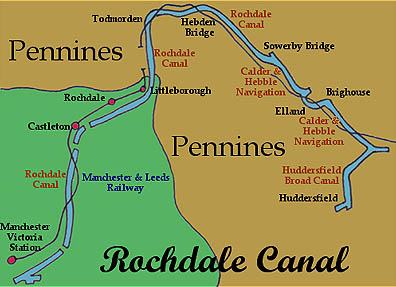

From perhaps as early as Roman times there was a route from what is now Yorkshire over Blackstone Edge. The image above generously donated by Vincent Lowe, shows the "Roman Road" that can be seen today on those lonely moors. Over the years the pack-horse routes were transformed into roads like the A58 which links Rochdale and Halifax. Transportation by road in the Rochdale area improved with the building of the low-level turnpike road from Littleborough up the Roch Valley to Tordmorden. This road was known as the Gale Road after the village of Gale, north of Littleborough. In 1804 the Rochdale Canal opened from Manchester, through Rochdale and across the Pennines to Sowerby Bridge where it joined the Calder and Hebble Navigation and on into the Huddersfield Canal. Multiple locks fed by a number of reservoirs carried narrow boats across the border from Yorkshire into Manchester where they could join the Bridgewater Canal.

The Rochdale Canal was

part of a growing network of canals that were created

to open up a transportation route from the North Sea

at Hull to the Irish Sea at Liverpool. In all it took

ten years to complete the Rochdale Canal. Work began

in 1794 and construction was going on in three

distinct segments.   The first section from Sowerby Bridge to Todmorden was completed in August, 1798. The Todmorden to Rochdale portion, over the summit at 600 feet, was finished by December of the same year. The final stretch from Rochdale to Manchester took 4 more years to build. The completed canal, which actually opened to traffic in 1804, comprised 92 locks, 6 bridges, 8 aquaducts and a 70 yard long tunnel. The canal enjoyed more than three decades of virtually unopposed supremacy as the transportation route of choice before Stephenson completed his Leeds to Manchester Railway in 1841. Stephenson's railway followed the same route across the Pennines that the Rochdale Canal had used. However, whereas the canal had avoided using a long and expensive tunnel by building multiple locks, Stephenson built, what was at the time, the world's longest railway tunnel, the 1.6 mile long Summit Railway Tunnel.

By modern standards the

Summit Tunnel is a modest excavation. At approximately

a mile and a half in length, it is dwarfed by the

Channel Tunnel and the road and rail tunnels in North

America and Europe.

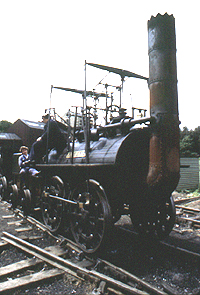

23,000,000 bricks were used in the construction of the tunnel. When construction was in full flight, the brickies were laying 51,000 to 60,000 bricks a day. Many of these bricks were made in the vicinity of the tunnel by women and children toiling in all weather conditions in open brickyards. Bricks were made by hand in cheap wooden forms. At the end of a long hard day, often lasting from sunrise to sunset, the women and their children returned exhausted to their primitive slum dwellings. The cement use to bed the bricks in the tunnel was known as Roman Cement. It was so named because of its similarity to the cement used by the Romans, and was selected because of its impermeability to water. 8,000 tons of dry cement were transported from Hull by canal to the tunnel site. When the Channel Tunnel was constructed, it was obviously extremely important that it be straight, especially since it was being built from both sides simultaneously. Laser technology was used to ensure that the digging machines stayed on the required path. The builders of the Summit Tunnel used wooden towers on the moors to lay out the line for the ventilation shafts and below in the excavated cavern candles suspended from the shafts were used to align the tunnel. Not including the people employed by the brick-makers, there were an average of 1,000 men and boys working on the tunnel at any one time. The workforce fluctuating from 800 to 1,253 at various stages in the construction. The first contract for the tunnel was signed in September of 1837 and the tunnel opened officially on March 1, 1841. The final cost for the tunnel was £251,000. The human cost was even higher since 41 men died during the building of the tunnel, an equivalent of one life for every 70 yards gained.  The kind of locomotives

that would have been running along the Leeds

& Manchester Railwaythrough Rochdale in

1841.

The tunnel

proved to be much safer as a transportation

route than a construction site. During its 160

years of operation there have only been 4

accidents in the tunnel. The first accident

happened just two years after the opening. On

that occasion wagons were damaged but no one was

injured. The following year a Leeds to Liverpool

passenger train derailed in the tunnel and 10

passengers were "shaken up". The most

spectacular accident occurred on December 20th

1984. A frieght train entered the tunnel in the

early hours of the morning. The locomotive was

pulling 13 bulk tankers containing 780 tonnes of

four star petrol enroute from Middlesborough to

Warrington. Half a mile into the tunnel a

defective axle-box bearing caused the fourth

tanker to derail bringing the train to a halt.

The train crew had only the light from the

locomotive to illuminate the tunnel and they

were facing ahead not backwards along the

disabled train. What they could see though were

flames caused by burning fuel that had leaked

into the ballast under the opposite track. When

they heard a whooshing noise, the crew ran to

safety along the remaining mile of tunnel to the

village of Summit where they raised the alarm.

The struggle to control the Summit Tunnel fire involved 200 firefighters and many acts of heroism, including the re-entry into the tunnel by the train driver and two guards to retrieve the locomotive and three undamaged tankers, despite the presence of thick smoke and couplings that were now too hot to handle. Smoke billowed from an air vent and suddenly became very dark. Instantly, a huge fireball shot out of another air vent following an explosion that shook the hill. Afraid that a catastrophic explosion might result in a fireball that would travel along the tunnel, a fleet of emergency vehicles were dispatched to evacuate upwards of 200 people living in the vicinity. Despite the size of the

fire-fighting response and the sophistication of their

equipment, the fire was soon out of control and in the

end took 3 days to burn itself out. Firefighters,

pouring expansive foam down the two air shafts closest

to the fire, almost certainly prevented the blow-back

along the tunnel that everyone was afraid would

happen. It was 8 days before British Rail engineers

could get into the tunnel to inspect the devastation,

which included a quarter of a mile of buckled track

and lining bricks that had melted in the fire. It was

8 months before trains ran through the tunnel again.

Two days before the tunnel was re-opened to traffic, a

charity walk was organized and 5,500 people walked the

mile and a half through the rehabilitated Summit

Tunnel.  Above the railway as it passes

through Littleborough.

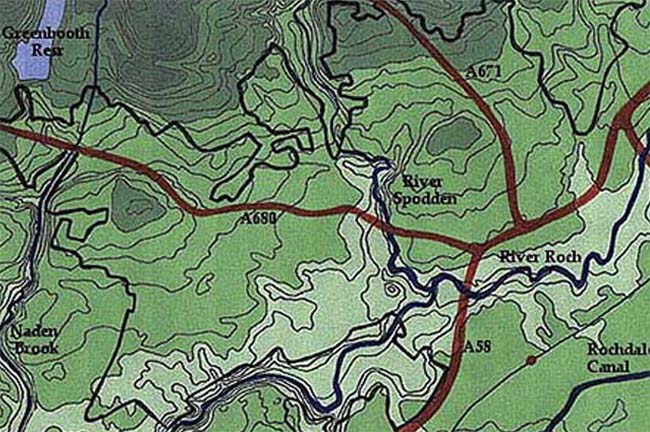

The sketch-map below shows the topography of the area around Rochdale. The black line marks the boundary of the built-up area of Rochdale in 2001. You can see from the map how the transportation routes - road, rail and canal - took advantage of the natural layout of the land.  In 2018, Rochdale is served by bus, tram and train services.  Above: Rochdale Railway Station In the town centre a new bus

station and tram stop are located across from each

other on Smith Street.

Above & Below: Rochdale Bus Station   Above & Below: Trams stops in Rochdale  ********************************* The image of the Roman

road is shown with the permission of Vincent Lowe. The 4 images of the

Rochdale Canal are shown with the permission of Martin

Clark

and come from his Virtual Tour of the Rochdale Canal web site. |

||||||||||||