The House

of Recovery

In his book, "The

Condition of the Working Class in England", published in

1845, Friedrich Engles says this about the living

conditions in England's cities, "The

manner in which the great multitude of the poor is

treated by society today is revolting. They are

drawn into the large cities where they breathe a

poorer atmosphere than in the country; they are

relegated to districts which, by reason of the method

of construction, are worse ventilated than any others;

they are deprived of all means of cleanliness, of

water itself, since pipes are laid only when paid for,

and the rivers so polluted that they are useless for

such purposes; they are obliged to throw all offal and

garbage, all dirty water, often all disgusting

drainage and excrement into the streets, being without

other means of disposing of them; they are thus

compelled to infect the region of their own

dwellings....... What else can be expected than an

excessive mortality, an unbroken series of epidemics,

a progressive deterioration in the physique of the

working population?"

The conditions that

Engles described were typical of the area south of

Portland Street in the late 18th Century. In an

article entitled "The Manchester 'House of Recovery'",

published in the Medical School Gazette in 1825, D Sage

Sutherland MD says that the area, "consisted of

miserable hovels, with cellar dwellings." He adds

that, "Silver Street ... was the principal source of the

infectious cases, and as many as 400 cases of typhus

were removed from this street between September 1793 and

May 1794."

To address the needs of the people of the area a "House of Recovery" was established on Portland Street across from the Lunatic Asylum.

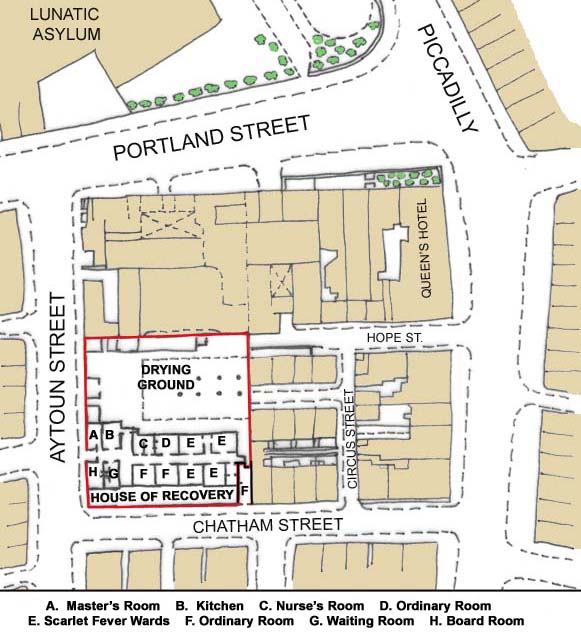

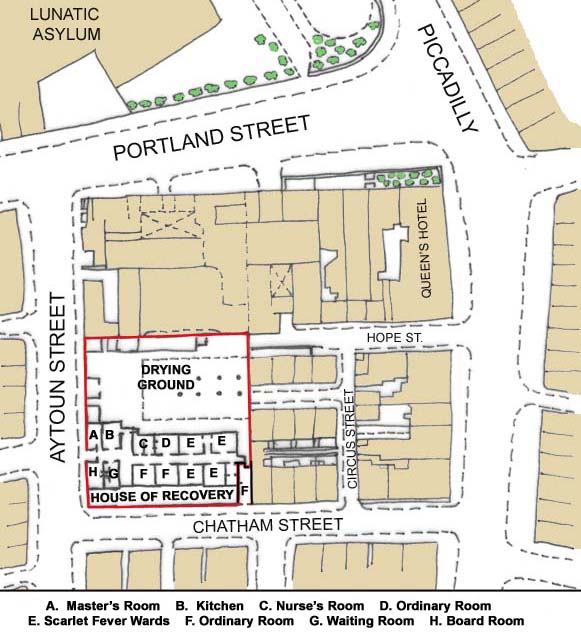

When those premises were seen as unsuitable they became a livery stable and the House of Recovery moved to a site on the corner of Aytoun Street and Chatham Street, opening for patients in 1804. The main frontage was on Chatham Street but the entrance was on Aytoun Street. The plan below shows the layout of the building.

In Sage Sutherland's article he refers to annual reports from the House of Recovery and points out that from the opening of the institution in 1793 until 1823, "10,870 persons were restored to health, and it certainly cannot be any exaggeration to say ten times that number of persons have been rescued from the danger of contagion by the removal of the infected person to this asylum for the diseased, where instead of the damp, noisome and often crowded and dirty cellars or garrets from which they had been brought, they were placed in a clean well-ventilated apartments, with everything at hand to assist nature in repelling the disorder."

"In addition to what were designated ordinary fevers, namely, typhus and typhoid, a special provision was now made for scarlet fever, smallpox, and measles." There was a large open courtyard which, "contained a railed-off area, with masts for the disinfection of infected clothing by sunlight and air, and for drying purposes."

To address the needs of the people of the area a "House of Recovery" was established on Portland Street across from the Lunatic Asylum.

When those premises were seen as unsuitable they became a livery stable and the House of Recovery moved to a site on the corner of Aytoun Street and Chatham Street, opening for patients in 1804. The main frontage was on Chatham Street but the entrance was on Aytoun Street. The plan below shows the layout of the building.

In Sage Sutherland's article he refers to annual reports from the House of Recovery and points out that from the opening of the institution in 1793 until 1823, "10,870 persons were restored to health, and it certainly cannot be any exaggeration to say ten times that number of persons have been rescued from the danger of contagion by the removal of the infected person to this asylum for the diseased, where instead of the damp, noisome and often crowded and dirty cellars or garrets from which they had been brought, they were placed in a clean well-ventilated apartments, with everything at hand to assist nature in repelling the disorder."

"In addition to what were designated ordinary fevers, namely, typhus and typhoid, a special provision was now made for scarlet fever, smallpox, and measles." There was a large open courtyard which, "contained a railed-off area, with masts for the disinfection of infected clothing by sunlight and air, and for drying purposes."

Until 1820 the average

number of patients admitted to the House was about

360. In 1847 though, the year of the Potato

Blight, those numbers soared to 955 and in 1848 to

1,049. "Scurvy became prevalent in

Manchester and was followed by a serious outbreak of

dysentry and a still more alarming epidemic of typhus

and typhoid fever."

The House of Recovery on Aytoun and Chatham Streets continued to operate until 1850 when depleted funds and declining case numbers prompted the trustees to transfer their operation to the nearby Manchester Royal Infirmary and to sell the site of the building.

In 1867, the architectural practice of Mills and Murgatroyde built a cotton warehouse on the site of the House of Recovery for A. Collie and Company. Thirteen years later it was converted into the Grand Hotel.

The House of Recovery on Aytoun and Chatham Streets continued to operate until 1850 when depleted funds and declining case numbers prompted the trustees to transfer their operation to the nearby Manchester Royal Infirmary and to sell the site of the building.

In 1867, the architectural practice of Mills and Murgatroyde built a cotton warehouse on the site of the House of Recovery for A. Collie and Company. Thirteen years later it was converted into the Grand Hotel.

Today the former Grand

Hotel is an upmarket apartment block, refurbished and

remodelled by the architect Ian Simpson, see below.