|

Water

Street Railway Bridge

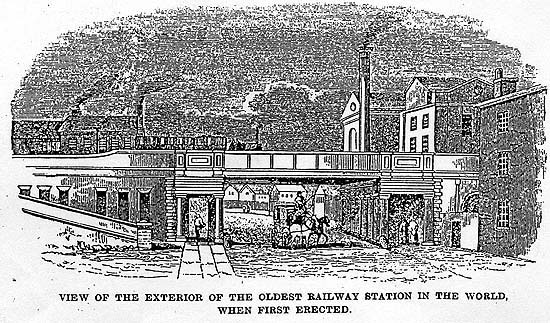

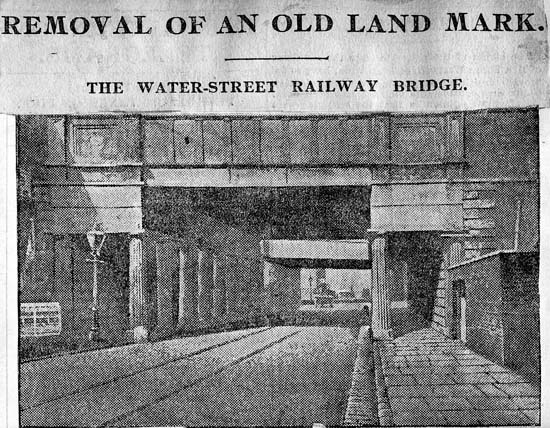

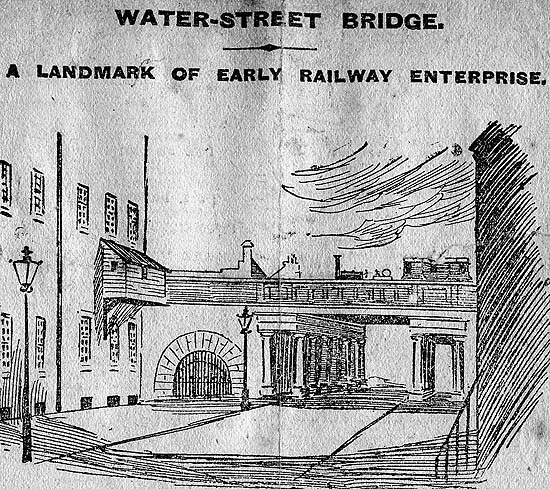

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the first railway to carry passengers between two cities on a scheduled basis and powered by steam. Its construction involved overcoming a number of geographical challenges and required the engineers to construct 64 bridges and viaducts, all of which were built of brick or masonry. When the railway first arrived in Manchester, the terminus was actually on the Salford side of the Irwell. However, eventually a piece of land was located close to the canals of Castlefield for a station and sheds. One last challenge was the crossing of Water Street. This was achieved by the construction of a cast iron beam girder bridge by William Fairbairn and Eaton Hodgkinson. It was cast at their factory in Ancoats.  The old print above shows the original Water Street railway bridge and the Water Street station. The photograph below is shown with the permission of Chetham's Library. It shows the bridge on the far left.  That bridge sat at this point on

Water Street until 1904 when it was replaced by the

one you see below.

Roger Nash contacted

me some time ago about his Great Grandfather, William

Wilson who worked as Chief Bridge Inspector and who

supervised the demolition of the Water Street

Bridge. Roger had his great grandfather's

notebook which contained an account of this event.

Roger said of the

information in the notebook: "This account has

been taken from his hand-written reminiscences,

written sometime after the newspaper articles, and

clearly mostly taken verbatim from them. A copy of the

article from Manchester Evening News, August 26th 1904

is the source of the second half, itself written long

after the events described. William makes his

role in the work clear at the end. His reference to

the parks is verified in an undated article in The

Railway Magazine, acquired from the Museum of Science

and Industry.

(The illustrations shown below were included in William Wilson's information on the demolition of the bridge) William Wilson retired from the railway in 1908. ********************************

“The fate of the old

bridge over Water-street around which a good many

historical associations cluster, will be decided by

vote of the City Council today. Repair or rebuilding

has become absolutely necessary, and the L. and N.W.

Railway Co say that, inasmuch as repairs costing £750

will meet their purposes and that rebuilding will

effect an important street improvement and will cost

£4,000 if the latter course is to be adopted the City

Council should pay £3,250.

The proposal appears on the face of it to be a fairly cool, not to say impudent one and it is not surprising that the Corporation which has the matter in hand has pronounced against it. If the City Council did adopt it the railway company would get an entirely new bridge calculated to last a century or more for the small sum which they estimate it would cost to provide new girders and decking. The £4,000 estimate includes the removal of the whole of the old structure with the columns and projecting piers and the substitution of a new flat steel girder bridge giving a clear width of roadway of 16 yards. The history of the Water-street bridge takes us back to the earliest days of railway construction. Most people are aware that the famous Liverpool to Manchester line, built in the closing years of George the fourth’s short reign, was the second in England. Its predecessor was the Stockton to Darlington Railway which owed its initiation to the enterprise of George Stephenson and of Mr Pease. In those early days what we now recognise as the most absurd prejudice had to be overcome. George Stephenson was wont to say of his difficulties at that time:- ‘Matter gives me no trouble. I can bend it to my purpose; it is mind which is my great difficulty. I cannot engineer that.’ Opposition was in fact so violent and unreasoning that Stephenson carried out his survey in the face of every conceivable difficulty barely escaping personal injury and the seizure and destruction of his instruments. Even when the line was finished Stephenson and his friends had a hard struggle to prevent it being opened with horse traction or stationary engines and ropes. It was intended when the line was first prospected that it should have its terminus at Salford but subsequently it was decided to bridge the Irwell and Water Street, and to run into the heart of Manchester. The design of the Water Street Bridge seems to have enraptured many contemporary scribes. Perhaps we are less imaginative in these days, or familiarity has bred contempt. Certainly we should not find in the gloomy aspect of the structure from the roadway beneath much resemblance to an elegant classical temple. Yet that is the idea which those rows of Doric columns bordering the footways conveyed to one writer of the period. ‘There were 11 Doric columns on each side the footwalks below which form colonnades and gave the interior the appearance of an elegant classical temple the parapet is of cast iron enriched with pilasters and neatly empanelled.” Source

unknown, possibly Manchester Evening News, earlier

date than that below.

********************************

The

Manchester Evening News August 26th 1904 had

the following report referring to this Bridge with a

photo, showing the above remarks, as follows “Workmen

are at present engaged in demolishing the old bridge

which spans Water-street. This structure is one of the

oldest railway bridges in this country. It consisted

of stonework carried on fluted columns at each side of

the roadway near to the kerb line and cast iron

girders over the roadway. The following is a

description of the bridge written in 1830:- ‘The

railway crosses Water-street by a beautiful, flat

bridge, supported by cast-iron beams arched between

with brickwork, and partly by a row of eleven Doric

columns on each side of the footwalks, below

which form colonades, and give the

interior the appearance of an elegant classical

temple. The height is 17½ ft., and the castings,

by Messrs Fairbairn and Lilly, weigh 45 tons. The

parapet is of cast iron, enriched with pilasters and

neatly empanelled.’

A few years ago, when Alderman Vaudrey was Lord Mayor of this city and Chairman of the Improvement Committee, he entered upon negotiations with the late Mr Stephenson, then Chief Engineer of the London and North-Western Railway Company with the object of getting a new bridge of greater span, and the widening of the roadway and carriageway of Water-street in continuation of the general scheme for the widening of that thoroughfare. The negotiations were conducted by the present Chairman (Councillor J R Wilson), and resulted in an arrangement being come to by which a new structure is now being erected at the joint cost of the Corporation and the railway company. The New Structure The new structure will

be of steel, and there will be a clear span or width

of roadway beneath of 48 feet. The present roadway

under the bridge is only 24 feet 6 inches wide, with a

footway on each side of the bridge inside a row of

stone columns, 5 feet 6 inches wide. The abutments of

the new bridge will be lined with white glazed bricks

with plinths of coloured brickwork. The headway will

be 17 feet. The bridge which is now being removed was

designed by that great pioneer of railway engineering,

George Stephenson, who engineered the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway. On the 29th October, 1824, a

prospectus was issued advocating the construction of

the Manchester and Liverpool Railway, of which the

Water-street bridge afterwards formed a part, and in

this circular we find such names among the Manchester

representatives as Barlow, Potter, Sharpe and Garnett,

well-known Manchester citizens of that day.The line of

railway as at first designed was to run from

Manchester to Liverpool via Chat Moss and through St

Helens and Knowsley, and to enter Liverpool on the

north side. The Bill was vigorously opposed by Lord

Derby and others, and was ultimately thrown out by the

Parliamentary Committee.”

This Bill ultimately received the sanction of Parliament but the difficulties of the engineer were only then beginning. The road over Chat Moss “caused an immense amount of trouble. It was referred to at that time as the ‘Valley of Desolation’ and when the work of constructing a line across it were commenced ‘it’, to use the words of the engineer, ‘engulfed and swallowed everything; ballast, casks, and hurdles sank into the shades of eternal night.’ The directors became uneasy about the cost and the slow progress of this part of their enterprise, and a special meeting was called to consider whether they should give up the construction of the line. Stephenson, however, recommended the directors to persevere, and one of them said to him after the meeting in 1829, ‘Now, George, thou must get on with that railway and have it finished without further delay. Thou must really have it finished by the beginning of the New Year.’ Stephenson referred him to the heavy character of the works and want of money, the wet weather etc, and said it was impossible. The director retorted, ‘I wish I could get Napoleon to thee. He would tell thee there is no such word as ‘impossible’ in the vocabulary.’ ‘Tush’, said Stephenson, ‘give me men, money and materials and I will do what he could not do – drive a railroad from Liverpool to Manchester over Chat Moss.’ Opening of the Line The railway was finally opened for traffic on the 15th September 1830.” ******************************

An interesting

Reminiscence

An old man, a

respected citizen of Manchester told the writer [

newspaper reporter] that he was present at the opening

of the line and was then nine years old. He states

that he well remembers the celebrations on the 15th

September 1830. “The day was cloudy and drizzly and he

viewed the procession from Ordsall Lane, where the

train, which conveyed amongst others, the Duke of

Wellington, stopped. One of the things which made most

impression upon his juvenile memory was the carriage

in which the Duke travelled. The doorway of the

carriage was surrounded by an assembled multitude,

eager to shake hands with his Grace. The carriage was

square, something like a box, covered with a

crimson cloth with a bold gilt moulding. The same

gentleman also remembered Dr Ransome, a great

surgeon of that day, leaving Ordsall Lane on the

Engine for Liverpool to attend a Mr Huskisson, who it

will be remembered met with an accident through

leaving the train whilst it was in motion.”

The reason that I have given the particulars referred to in the back pages [is] that I have been greatly interested in the work as Chief Bridge Inspector particular of [sic] having the honour of superintending of taking down the Bridge at Water Street, it being one of the first Railway Bridges erected by the famous George Stephenson and replacing the new Structure with Steel Girders & floor plates. The old bridge had been well built and the material used was of the best of course. It was proposed that the Bridge and stone Columns should be reused in some of the Parks in Manchester so as we took it down we carefully loaded up and unloaded the same upon spare ground at Levenshulme. William Wilson 1844-1931 |